Australian gold miner, St. Barbara, ceased production in January after exhausting the gold at the Touquoy mine in Moose River, Nova Scotia. After it finishes processing stockpiles, it will be putting the mine in care and maintenance mode.

Care and maintenance is an in-between state where the mine isn’t active or closed. There is still some monitoring for safety and the environment, but it holds the mine in limbo.

Mining companies in Nova Scotia have to set aside a ‘reclamation bond’ prior to production. This is a separately held security specifically for mine reclamation that can be adjusted based on mine activity. In the case of the Touqouy mine in Nova Scotia, the pricetag was $41.2 million. However, if the company declares bankruptcy while the mine is in care and maintenance mode, the bond will never activate. Consequently the mine will be left in perpetual limbo.

The consequences of perpetual care and maintenance could include environmental contamination, vandalism and theft.

It’s a situation Karen McKendry, the wilderness outreach coordinator with environmental charity, Ecology Action Centre, is intimately familiar with. McKendry suggests Nova Scotia taxpayers should be wary given the circumstances surrounding the Toquoy mine because of something similar that happened in New Brunswick. Trevali Mining (TSXV: TV), which owned the Caribou mine 50 kilometres west of Bathurst, declared bankruptcy while the Caribou mine was in care and maintenance mode. Now the cost of the cleanup is being foisted on the taxpayer.

Abandoned mine in Larder Lake, Ontario. Image from Magnolia677 via Wikimedia Commons.

“The kind of thing that regularly happens when mines go on care and maintenance, whether they stay in the same company or perhaps switch hands, ultimately a lot of companies declare bankruptcy in that time period,” said McKendry, in an interview with Mugglehead.

McKendry said the care and maintenance phase followed by a company bankruptcy is a fairly common sequence of events in the mining industry.

“There’s a purgatory where money and effort are not put forward,” McKendry said.

More regulation is required for care and maintenance of mines

She stated that more regulation is required for care and maintenance, including placing upper limits for care and maintenance before a final decision is made.

“A very practical thing we could do right now is, while the government is reviewing its environment assessment process, which holds the laws that dictate this, the process could be changed to have an end date for care and maintenance,” McKendry said.

“That is a practical thing that the government could do and people could call for right now.”

There are similar situations going on all over Canada regarding the mining industry and mine remediation in general.

“The mine isn’t considered closed, so the reclamation plan & the money to clean up the site… isn’t enacted. The N.B. government, & therefore taxpayers, got left holding the bag for caring for the [Caribou mine].”

-EAC's Karen McKendry#GoldMining

https://t.co/CcaVwcKP9o— Ecology Action Centre (EAC) (@EcologyAction) February 14, 2023

Mine remediation is the process of restoring a mine site to a condition that is safe for human use. Some components of reclamation include practices that control erosion and sedimentation, stabilize slopes, and repair impacts on wildlife habitats.

The final step is usually topsoil replacement and re-vegetation with suitable plant species.

Each province handles remediation legislation differently. The Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources regulates mine remediation for British Columbia. The ministry is responsible for setting and enforcing standards and regulations for mine remediation. It’s also responsible for monitoring and compliance with these standards.

Read more: NevGold submits exploration and expansion plans for gold project in Nevada

Read more: Nevada King assays show significant high grade intercepts at Atlanta Gold Mine Project

British Columbia retooled its reclamation security policy in 2022

The Government of British Columbia introduced an interim overhaul of its mining reclamation security policy in April of 2022. The change puts more responsibility on the companies operating in the province by requiring them to submit a plan covering the reclamation of the environment after closure.

Taxpayers would not be on the hook if a company declared bankruptcy during its development.

The policy includes changes to how the liabilities are calculated, and for how much reclamation costs miners are responsible.

Abandoned mine in Yellowknife. Image from TravellingOtter via wikimedia commons

Also, a reclamation security must be posted by any new mines and mines with under five years of remaining mineral reserves. The security includes both “conventional reclamation” like re-sloping and re-vegetation. It also includes environmental treatment, like the costs of operating and maintaining water treatment plants.

The government developed the policy as a response to a 2016 audit of compliance and enforcement in the mining sector. The audit report revealed the Ministry of Energy and Mines did not have enough security ($0.9 billion at the time) to handle the estimated environmental liabilities ($2.1 billion, then).

Read more: Calibre Mining gold discovery could breathe life into historic mining community

Read more: Calibre Mining budgets $29M for 2023 exploration in Nevada and Nicaragua

Government of Canada spent $1.14B on remediation in 2019

The proposed policy changes mitigate risk by requiring companies to pay before starting operations

The interim policy is not law yet. There is also a $1.14 billion difference between reclamation securities and liabilities. Additionally, the policy doesn’t provide provisions for disasters or bankruptcy.

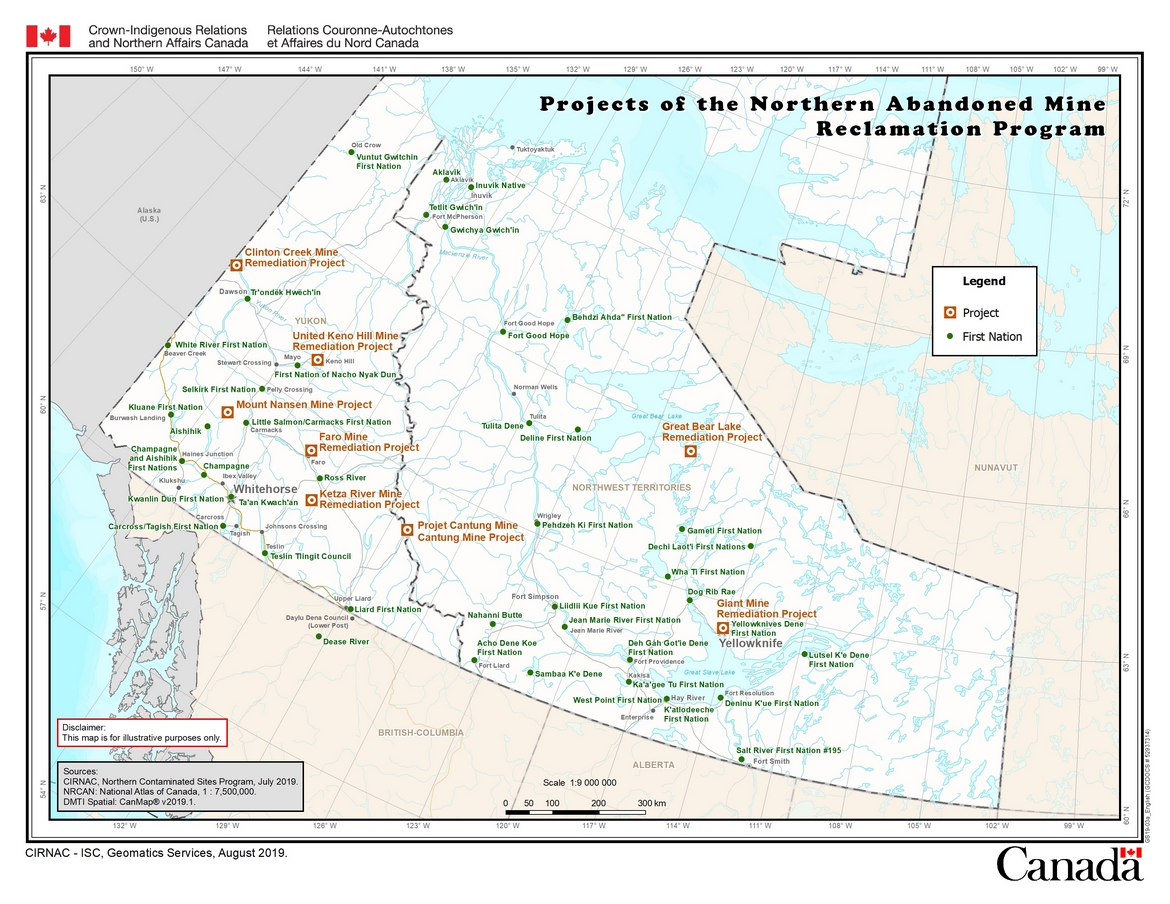

In the north, there’s the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation program. The program manages the remediation of 8 abandoned mines in the Yukon and Northwest Territories.

In 2019, the Government of Canada allocated $2.2 billion over 15 years to create the program, starting in 2020-2021. The program will remediate the largest and most complex contaminated sites in the north.

These are:

-

- Yukon: Faro, United Keno Hill, Mount Nansen, Ketza River, and Clinton Creek; and

- Northwest Territories: Giant, Cantung and the Great Bear Lake group of sites.

Active remediation of seven out of the eight sites will be completed at the end of the 15 year period. All sites will still likely require ongoing care and monitoring. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada bear responsibility for the active mediation of smaller sites and contaminated sites in the north.

Not everything has gone according to plan, though.

Read more: Calibre Mining increases mineral resources and reserves at its Nicaragua and Nevada operations

Read more: Barrick Gold hosts human rights watchdog at embattled Tanzania mine

Giant Mine is an environmental disaster waiting to happen

Giant Mine image. From Trevor MacInnis via wikimedia commons

Specifically, the Giant Mine, a former gold mine that operated between 1948 and 2004 within Yellowknife city limits has already run into a snag. Cleanup will cost taxpayers four times the original estimate.

The Treasury Board of Canada approved a $4.38 billion loan specifically for the remediation of Giant Mine in September, 2022.

Estimates in 2013 put the cost for the federally run project at $1 billion. However, those estimates did not take complications such as inflation and project management costs into consideration.

Also, remediation plans have since expanded. The original deadline posed for completion was 2031, but that deadline has since been extended to 2038. Additionally, that’s not taking into account the 237,000 tonnes of highly toxic arsenic trioxide dust stored at the site, which will require ongoing care and maintenance at significant cost.

The mine produced 220 tonnes of gold before its owner Royal Oak Mines went bankrupt and handed it over to taxpayers in 2005.

The legacy of the mine is its arsenic. Arsenic is leftover from the separation process of remove gold from ore. Now an estimated 13.5 tonnes of arsenic contaminated soil sits in huge piles underground. Arsenic dissolves extremely well in water. It would leach into the groundwater and enter nearby Great Slave Lake if left alone.

Meanwhile, years of study and debate concluded in 2014 that it would otherwise be too dangerous, difficult and expensive to remove the arsenic. Now it’s protected by 858 thermosiphons, or passively driven heat management systems using convection and conduction, to keep the rock at a stable temperature and freeze any water in place before it can escape.

Follow Joseph Morton on Twitter

joseph@mugglehead.com