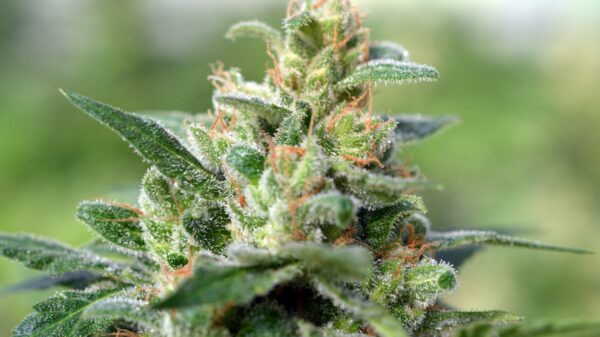

Zimbabwe was the second African nation to legalize the production of cannabis on the continent after Lesotho. The legislation was fast-tracked through parliament at a time when the industry was growing exponentially.

Observers applauded the move since Zimbabwe has a great climate and experience handling a controversial commodity: tobacco. But the nation is yet to get started, three years after legalization.

Zimbabwe is a country endowed with natural resources. It’s also notorious for getting in its own way.

When the government drew the initial regulations, it required participants to give a stake of the companies to the government and only farm on state land. That’s why a lot of the first movers are on state land. One such firm is Du Sud Cannabis Zimbabwe, based in Khami Prisons estate a few kilometres outside of Bulawayo.

But the government had to drop its request for stakes in companies, as international markets would frown on a “supplier that regulates itself on a controversial product,” according to Frian Dickson, managing director at Du Sud.

Its willingness to shift on the issue was proof that the “government is working very hard to make sure that all our needs are met.”

But very few of the country’s tobacco farmers could afford the move to cannabis because of production costs, Dickson continues.

Paul Mkondo in tobacco fields on his commercial farm in Mazowe, Mashonaland Central, Zimbabwe. Before his death in 2013, Mkondo was a businessman and political figure who fought for indigenization and Black economic empowerment in Zimbabwe. Image via Wikimedia Commons

According to the regulations set by the Medicines Control Authority of Zimbabwe, licensing requires prerequisite security measures that include a perimeter fence, motion detection, access control and constant visual monitoring. Producers also need to ensure that cannabis facilities are equipped with air filtration systems to prevent odours and pollen from escaping.

A barrier for many local farmers were licensing fees, which initially ranged from US$20,000–$50,000 — and that’s before initial capital costs. These expenses are why most licence holders are joint ventures between local and international investors.

At the end of 2020, the government dropped the fees for hemp to US$200 to become competitive but left the cannabis fees unchanged. Licensing fees for pot cultivation remain at US$50,000 for a five-year licence, which can be renewed for US$20,000. Renewal for hemp licences is another US$200.

“It seems as if international companies are more interested than local companies, but I think it’s to do with the fact that most locals who have resources such as land are not aware of the opportunities that come with cannabis production,” says Tendai Nyamidzi, a lawyer from Munvingi and Mugadza Legal Practitioners.

Read more: Lawmakers are keeping South Africa’s kasinomic cannabis economy in the shadows

Read more: South Africa’s cannabis bill is widely unpopular — here’s why

Kickstarting cannabis farming requires education, continued support from government

Switching farmers to cannabis will take a lot of investment and strategy from multiple sectors of the economy. Just as critical will be a unified and defined vision by the government. Currently, the regulation of medical cannabis is under the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare, while industrial hemp falls under the Ministry of Agriculture.

Tafadzwa DuToit Nyamande, head of business development at the Zimbabwe Industrial Hemp Trust, throws light on the task at hand.

“Hemp for fibre needs volume. Producers can’t do it from 10-hectare farms,” he says. “Hemp and tobacco are not friends — a tobacco farmer cannot be changed into a hemp farmer. Tobacco uses a lot of chemicals, and hemp does not require as many chemicals. In fact, it is not recommended to farm hemp where there was tobacco.”

“Hemp will soak up the chemicals, which is only good if you plan to clean or clear the soil. But for oils, CBD, edibles or anything that is in contact with the human body, the hemp has to be from clean soil.”

From his observations of the industry, Nyamande believes there needs to be education and awareness on hemp because the average Zimbabwean doesn’t know much about it. Tertiary institutions and industries affected by hemp like textile, plastic, construction and manufacturing also don’t know about hemp. As a result, a manufacturing and processing pipeline hasn’t been established.

Zimbabwe itself is a relatively small market overall. Recreational cannabis is still illegal, and medical cannabis use is still unclear. So most of the players in the Zimbabwean market will be exporting their products, whether it’s flower, oil or concentrate.

Industrial hemp cultivation in France. Image by Aleks via Wikimedia Commons

Portifa Mwendera, president of the Pharmaceutical Society of Zimbabwe, explains the retail situation and demand for medical cannabis: “Medicines are regulated under the Medical and Allied Substances Act and for cannabis read together with the Dangerous Drugs Act. So yes, there is a licensing process that any medicine will have to fulfill before it is sold to our citizens.”

“The use of medical cannabis is currently largely for clinical research purposes so much so that medicinal use is quite limited. Domestic interest is at a minimal,” he adds.

Du Sud isn’t planning on serving the local market. “Zimbabwe has not yet legalized cannabis for recreational use, so whatever we produce, we export from the flower, oil to the final product.” Dickson says

As it stands, many markets have become open to cannabis since Zimbabwe legalized medical use. However, further delays in establishing sound policies and overall economic reforms will cost it huge investments. And many still believe the government is doing a good job handling a new and controversial product.

“The production of cannabis was only legalized in 2018. It’s a new industry, and I’m of the view that our government is doing very well taking necessary steps to ensure that production of cannabis is effectively regulated,” Nyamidzi says.

Mwendera agrees. “The current legislation is adequate as it allows for cultivation and research into the plant’s medicinal benefits, which can be taken up by local researchers who have an interest in the benefits the oil may have on the health of a person.”

Zimbabwe’s climate ideal for cannabis, but policy presents roadblocks

Zimbabwe has a number of competitive advantages when it comes to cannabis. The climate, for one, is ideal for cultivation and can yield several harvests per year.

Land is also cheap and easily available, according to Nyamande, a World Bank OLC development finance alumni specializing in hemp and cannabis. Many farmers have large tracts of land without a cash crop.

“In Chikomba District, where I come from, people only wait to use their land once per year in the rainy season,” he says. “So for six months of the year, the land is idle. Hemp can grow in that time since it is a crop that isn’t a demanding crop when it comes to water.”

Dickson agrees. “Zimbabwe has the best climate for both indoor and outdoor cannabis farming, so you can choose to farm anywhere you want.”

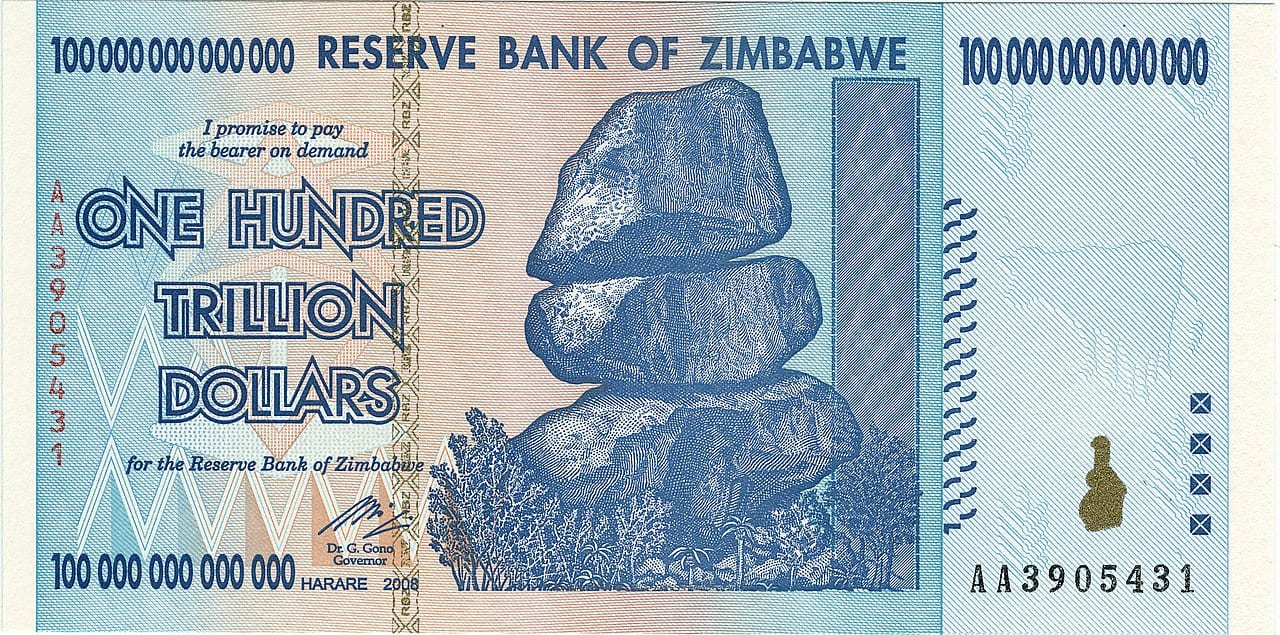

Although it has the climate for cannabis, Zimbabwe can be a challenging economic environment to operate within. Partly due to the complexities of setting up a new industry, but mostly because of government fiscal and monetary policy.

Establishing a cannabis industry is difficult. Nyamande notes that finding commercially viable seeds and making them cheaply available through distributors is a big hurdle towards mass adoption.

Dickson, on the other hand, has had to smooth over investor concerns about Zimbabwe’s business environment.

“The only challenge I got was to find an investor,” he says. “With the history of our country, many investors had a negative picture about Zimbabwe, so it was so difficult for me to really convince them that Zimbabwe was now open for business.”

One of Zimbabwe’s many economic issues revolves around how it manages local and foreign currencies. Early in 2020, in its assessment of the economy, the International Monetary Fund stated that “… uneven implementation of reforms, notably delays and missteps in [foreign exchange] and monetary reforms, have failed to restore confidence in the new currency,” referring to the Zimbabwe dollar introduced in 2019 to abolish a previous multi-currency system.

Poor monetary policy has led to massive inflation problems in Zimbabwe.

Monetary policy is at the core of Zimbabwe’s inflation problem. The year-on-year inflation rate ended 2020 at 348.5 per cent. In July, it reached a staggering peak of over 800 per cent.

But Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube surprised pundits when he projected cannabis exports of US$1.25 billion for 2021. Tobacco, the country’s biggest agricultural export, earned US$444 million from the 2020 marketing season. Considering that the government issued most of its cannabis licences in September of 2020, the projection left many people scratching their heads.

If licensees plant anything, it would be for testing or proof of concept. Nyamande provided clarity on the projection, saying that the figure came from optimistic business plans, not on actual demand.

That sentiment is shared by Dickson, who confirms, “The government asked all licence holders to submit their cannabis quota, so I’m sure that’s where they got it from.” Dickson’s cannabis operation is planning on planting only 10 hectares in 2021.

Correction (2021-7-3 12:45 p.m. PDT): An earlier version of this article quoted Nyamande as saying “In Komba District …” when he actually said “In Chikomba District …”