Illegal miners have begun operating inside a stalled, multi-billion-dollar gold project in northern Peru owned by the world’s largest gold producer, according to senior government officials.

Peru’s Prime Minister Ernesto Alvarez said Newmont Corporation (TSE: NGT) (NYSE: NEM) (FRA: NMM) has lost partial control of its Minas Conga project in the Cajamarca region to informal diggers. He told reporters Friday that illegal mining activity is already underway on the concession. Newmont did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

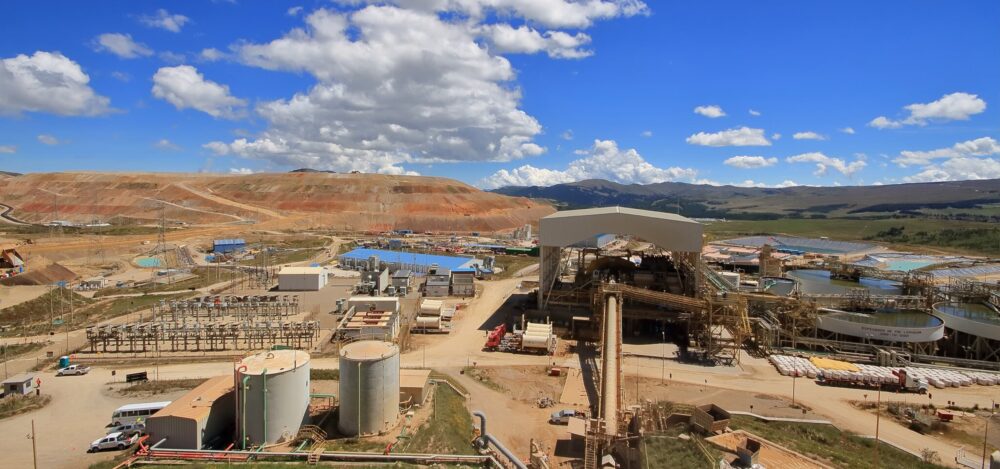

The project, valued at about USD$4.8 billion, has sat idle for more than a decade despite approved environmental permits. Development stopped in 2010 after strong opposition from farmers escalated into violent protests. However, Newmont retained its mineral rights even as construction plans collapsed.

Meanwhile, near-record gold prices have intensified pressure across Peru’s mining regions. Informal miners now see abandoned or delayed projects as open territory. Consequently, major operators increasingly face trespassing and resource theft.

Southern Copper Corp. (NYSE: SCCO), First Quantum Minerals Ltd. (TSE: FM) and MMG Ltd. have all reported illegal miners operating on their concessions. Additionally, those intrusions have delayed permitting, exploration and construction work.

Alvarez argued that stalled formal mining creates space for criminal operations. He said regulated projects impose strict environmental and labor standards, while illegal miners operate with none. Furthermore, informal mining often relies on mercury, which contaminates water sources.

The Conga site sits near river headwaters that supply surrounding agricultural communities. However, authorities now say those rivers show signs of mercury pollution from illegal gold extraction. Alvarez described the outcome as deeply troubling given earlier claims that agriculture required protecting the area.

Read more: NevGold delivers major growth at Idaho gold project

Read more: Antimony recovery results from NevGold’s Limo Butte project exceed expectations

Informal miners offered a legal pathway

Peru’s government also faces political pressure over how to respond. Officials recently supported extending Reinfo, a controversial permit that allows informal miners to operate under minimal oversight. Meanwhile, the country’s main mining industry group, SNMPE, strongly opposes the program.

Industry leaders argue Reinfo unintentionally shields criminal networks. They warn it discourages long-term investment and weakens enforcement. Conversely, supporters say the permit prevents social unrest by offering informal miners a legal pathway.

Newmont’s Conga project remains one of Peru’s largest undeveloped gold deposits. However, ongoing illegal activity further complicates any revival. Additionally, rising violence tied to informal mining has strained local policing capacity.

Government officials say enforcement alone cannot solve the problem. Subsequently, Peru must choose between restarting regulated mining projects or watching illegal operations expand deeper into contested regions.

Illegal mining has become a global problem, accelerating alongside high commodity prices, weak enforcement, and persistent rural poverty. Governments and companies across Latin America, Africa, and parts of Asia now struggle to contain informal and criminal mining networks that operate outside environmental and labor laws.

The problem extends well beyond Peru. In Ghana, illegal gold mining—locally known as galamsey—has polluted major rivers and forced the suspension of industrial operations. Mexico faces similar challenges, where organized crime groups increasingly control informal mining zones and use profits to fund broader criminal activity. Meanwhile, in Colombia, illegal mining frequently overlaps with armed groups.

Environmental damage remains one of the most severe consequences. Informal miners commonly use mercury and cyanide, contaminating water systems and farmland. Additionally, unregulated pits and tunnels increase the risk of deadly collapses, while deforestation accelerates erosion and flooding. Governments often lack the resources or political capital to enforce closures once illegal camps become entrenched.

.