According to one Vancouver Island farming duo, getting licensed by Health Canada has more to do with knowledge than money.

Katy and Shawn Connelly of Sea Dog Farm were able to get a micro-cultivation licence to grow cannabis on their five-acre farm for less than $15,000, making it possibly the least costly to date.

Based on their calculations of two outdoor harvests per growing season, they estimate being able to make upwards of $100,000 a year. If more farms like theirs followed suit, and if their predictions about consumers trending toward sustainable production are true, the business model could prove disruptive to an already unstable market.

But barriers to entry still exist, which the pair hopes to diminish by sharing what they’ve learned.

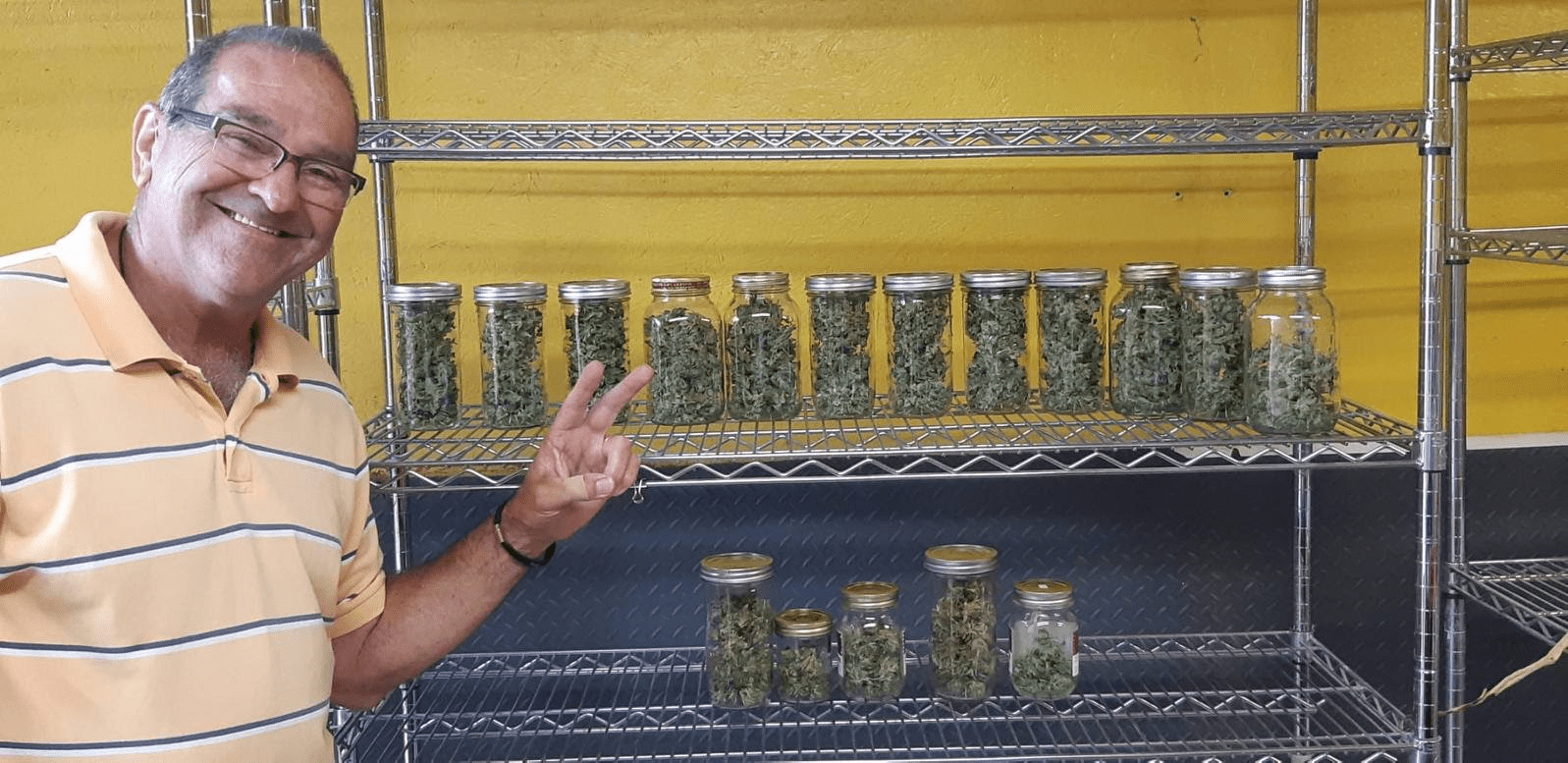

Katy with Shawn’s uncle Claude, who has multiple myeloma and has been their quality control expert. In its first two growing seasons, Sea Dog made about $12k a year in flowers, eggs and produce. They expect to triple those numbers, but the total would still not be enough to pay a living wage, they said. Submitted photo

In a presentation at last week’s Islands Agriculture Show, Katy detailed their licensing journey in a presentation aimed at fellow farmers. A video version of their story is also available as a three-part series on YouTube.

They said it took them about a week of labour to ready the field and drying room, but the licensing process itself took eight months from start to finish — and many hours of additional research on top of that.

“It doesn’t need to be that hard,” Katy said.

Throughout the process, Health Canada didn’t give the pair any specifics on how to fulfill the licensing requirements. The regulator would just parrot back the written requirements, Shawn said.

“I was at a meeting with Health Canada and the province,” Katy said, “who are both looking at ways to make more people decide to do this. I said you need more examples of the worst micro you are allowed to build outdoors, and the worst micro you are allowed to build indoors, and people can look and say ‘Oh, I can do that.’”

Showing people the “worst” facilities to get licensed would give people a clear idea of what Health Canada’s minimum requirements are.

By providing their example online, they hope to inspire others who have felt overwhelmed by the process and to introduce other farmers to the idea of cannabis as an additional revenue stream.

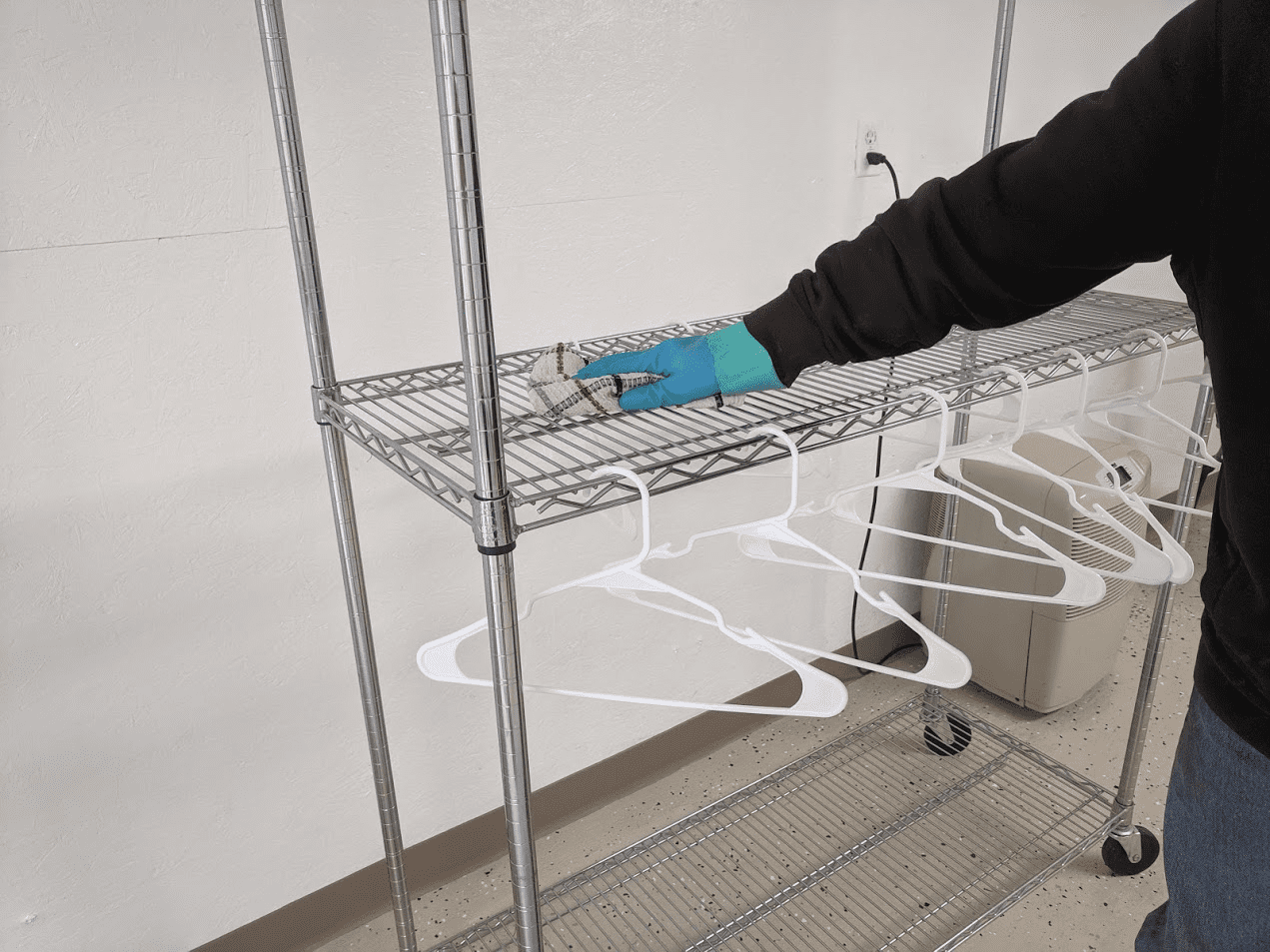

A lot of the licensing process involved sending very literal examples of how they intended to meet Health Canada’s requirements. Submitted photo

‘Municipalities are the biggest bottlenecks for micro-cultivators’

Especially in the early days of legalization, cannabis cultivation and food production were seen by many as at odds with one another.

The City of Delta expressed concern about the number of vegetable-growing greenhouses being bought out by cannabis companies, and Richmond called for a moratorium on cultivation on the Agricultural Land Reserve (ALR), a provincial zone of more than 11 million acres of land prioritized for agriculture.

At the time, major greenhouse vegetable growers including Houwelings and SunSelect converted millions of square feet to grow cannabis.

However, in the case of Sea Dog Farm, adding cannabis to their crop rotation could improve their ability to grow fresh local food by providing a living wage.

Farmers, especially aspiring ones, face challenges including hefty mortgage payments and steep competition from foreign markets.

Sea Dog has been refining its cannabis growing over the past two years. Katy and Shawn have decided to use auto flower seeds, which flower at a fixed interval rather than depending on the external light cycle to change. Beardless Claude pictured above. Submitted photo

But right now Katy says municipalities are the biggest bottlenecks for micro-cultivators.

“Municipalities have the greatest opportunity in decades to encourage food production on small farms,” she said.

Her advice to municipal governments is to let farmers dedicate up to 10 per cent of their land to grow cannabis. Sea Dog Farm didn’t have to get permission because it’s growing outdoors on the ALR, but Katy and Shawn have only converted 1/20th of an acre to pot production.

If the other 90 per cent of farms’ growing space had to be food, Katy says it would eliminate a lot of the problems in the Lower Mainland with vegetable farmers displacing their entire crops with cannabis.

“We need to focus on the food as well as the cannabis,” she said.

nick@mugglehead.com

@nick_laba